Remembering Herman Wouk

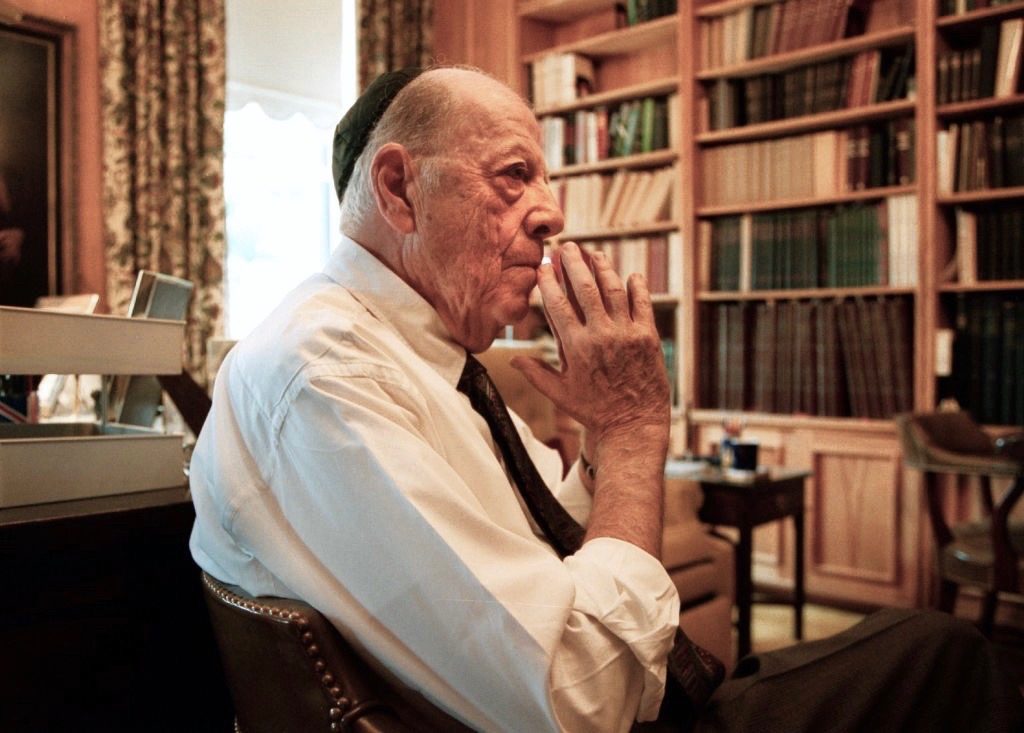

Herman Wouk in his home office in Georgetown, Washington, DC, in 2000. Photo: James A. Parcell/The Washington Post/Getty Images

As a purposeful part of our family-rearing strategy, Susan and I never owned a television set. Yet we didn’t miss a single one of the nineteen episodes of the two-part television series The Winds of War and War and Remembrance. Those staggeringly ambitious productions were brought to the small screen by the late great director and producer Dan Curtis. They were faithfully based on the two novels of the same names by the immortal Herman Wouk. In my view, all Jews whose paramount element of identity is commitment to Torah Judaism should read those two novels or, at the very least, watch the nineteen television episodes. It would make a wonderful family activity and would stimulate serious conversation.

The reason I feel this way is because Wouk, who not only authored the two novels but also worked on the thousands of pages of screenplay needed for the miniseries, was such a Jew. Thankfully, today Torah plays a part in the lives of many of our people. Along with family, work, and perhaps politics and tennis, Torah takes its place; but for quite a few of us it is sadly not paramount. Many of us are perhaps more observant than we are religious—the two don’t necessarily correspond. Large numbers of us Orthodox Jews attend synagogue and generously support Jewish causes, but our worldview is shaped by our education and social milieu rather than by the Torah. We attend a Torah study shiur similarly to how we say a berachah or put on tefillin; that is to say, as a religious obligation rather than as an irresistibly breathtaking glimpse into the mind of HaKadosh Baruch Hu. But for Wouk the Torah was the paramount element of his identity.

–OU Board Members and NCSY veterans Vivian and Dr. David Luchins

How do I know? Because while the television series Winds of War and War and Remembrance were in production in Hollywood during the 1980s, Wouk spent a great deal of time in Los Angeles. While there he selected as his spiritual base the Pacific Jewish Center (“The Shul on the Beach”), which I had the privilege of serving as founding rabbi. Veracity compels me to confess that whenever Wouk strode into our beachfront shul on a Shabbat morning, my heart sank. Although I invested many hours preparing and polishing the fifteen-minute devar Torah I delivered each Shabbat morning, the presence of the great author did intimidate me. My anxiety was just as severe on those occasions when he attended my Monday night Chumash shiur. You might well assume that my unnerved reaction to Wouk’s presence was due to my having read and revered The Caine Mutiny, Marjorie Morningstar and the aforementioned two masterpieces, and being awed by the presence of their author. Furthermore, for many years I had been consistently recommending and giving away numerous copies of what I still regard as one of the finest depictions of Judaism, Wouk’s This Is My God. It is true; I did admire him greatly, but my discomfort when he attended my teaching was not the result of being starstruck.

I found Wouk’s presence daunting because he seemed as familiar with the Torah material as I was. What is more, during our conversations following my presentations, he probed with profound curiosity into deeper repercussions of everything I had said. His observations, often supported by a gemara here or a midrash there, frequently raised issues I had never considered. But here is the thing. Unlike the long-ago yeshivah-educated worshipper who can be found in every synagogue and who regularly buttonholes the rabbi with endless picayune details on the way to kiddush, this was entirely different. It was clear to me that to Wouk, nothing was more important than gaining clarity into God’s message to mankind—the Torah. It was equally obvious that he had never adjusted his view of Torah to make it fit his worldview. On the contrary, his perspective on the world, politics, his craft and art in general was an organic consequence of his Torah learning. Wouk—the Jew, the man and the author—were all shaped by his commitment to the Torah. He may have intimidated, but above all, he inspired.

Dr. Henry Kressel recalls that getting into Wouk’s course was no simple feat. “A lot of students wanted to get into that course,” says Dr. Kressel. He selected only five students each semester. “Taking that course was an experience you don’t forget.”

The following mishnah resonated powerfully with him. We learned it together one Shabbat afternoon:

Rabbi Shimon said: If one is studying while walking on the road and interrupts his study and says, “How fine is this tree!” or “How fine is this newly ploughed field!” the Torah considers him as if he was mortally guilty (Avot 3:7).

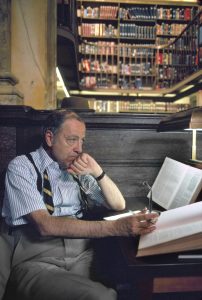

Author Herman Wouk works on a sequel to his bestselling novel in the Library of Congress, District of Columbia. Photo: Dick Durrance II/National Geographic/Getty Images

The mishnah is not condemning our appreciation of nature’s beauty. On the contrary, it is criticizing a worldview in which enjoying Hashem’s creation demands an interruption from Torah. Instead, we are required to see every aspect of the world, its cities and its swamps, its factories and its forests, unified with its Biblical Blueprint as one seamless symphony of holiness. I so clearly remember Wouk laughing aloud in irrepressible joy at this affirmation of his faith.

On one Shabbat that he shared with us, one of our guests asked why my wife and I did not invite each of our children to contribute some thoughts on the sedra of the week, nor did I devote a few moments of the meal to a formal devar Torah. I explained that to do either of those two things would be to acknowledge that the rest of our table conversation had nothing to do with Torah and that we therefore had to sneak in a few minutes of pro-forma Torah discussion in order to rescue ourselves from the terrible indictment of a meal without Torah conversation, expressed in another mishnah (Avot 3:3). I explained that at our Shabbat table we never discussed people or even things, but only ideas; and whether we explored ideas in science, art, sociology, economics or politics, we were always inevitably measuring them against the timeless, incandescent truth of Torah. In other words, we tried to ensure that all conversation at our table was Torah. Wouk seized the opportunity to happily repeat the meaning of Rabbi Shimon’s mishnah in Avot about the beautiful tree. This was evidently something he had long ago incorporated into his relationship with HaKadosh Baruch Hu and he could scarcely conceal his delight at sharing the Torah as a comprehensive matrix of all reality.

–OU Honorary Past President Rabbi Julius Berman

That we should find innumerable references to his conviction of the Torah as the key to everything in This Is My God is hardly surprising. It is after all his eloquent panorama of Judaism as well as a testament to the depth of his own faith in Orthodox Judaism that he wrote back in the 1950s. Naturally he wrote sentences such as, “I also believe in the law of Moses as the key to our survival.” Or, “Nor do I understand Zionism without Moses as anything that can long endure.” But what is far more revealing of his deep conviction is that even his unforgettable Marjorie Morningstar contains passages like this one uttered by Noel Airman, who had changed his first name from Saul in order to conceal his Jewishness:

It turns out in the end that all economic practices are really produced by the religious beliefs of a society—and that all of economics, all the central questions—money, rent, labor, everything—are part of applied theology.

Back in 1954, Herman Wouk served as the keynote speaker at the OU convention, where he endorsed creating a new youth movement to stem the frightening tide of assimilation: NCSY. Seen above: Wouk is in the middle photo in the pages of Jewish Action, then an internal newsletter of the OU.

One could argue whether the Gemara’s reluctance to impose price controls (Bava Batra 89a) endorses a free-market economy or whether the Torah’s concern for our destitute brother (Deut. 15) encourages a welfare state, but what is beyond question is that the Torah contains many more rules concerning money and property than it has regulating kosher food. It is also true that no foundational documents of any of the world’s man-made religions are as concerned with matters of economics and finance as is the Torah. Yes, even Noel Airman, (Luftmensch in Yiddish) in a novel about a young Jewish girl from the Upper West Side of Manhattan trying but failing to escape her Jewish identity, must articulate Wouk’s awareness of the Torah as the key to everything.

We see Torah themes of teshuvah (atonement) and hakarat hatov (acknowledging good done for one) in The Caine Mutiny.

It goes without saying that in Winds of War and War and Remembrance, it is not only in the haunting words of Berel and Aaron Jastrow that we see Wouk’s clear view of a world in which only Hashem is in charge. Almost all of the nearly two thousand pages carry the subtext of Wouk’s world, unified by God and His Torah. The subtext is every bit as lucid as the narrative.

An announcement of the release of Wouk’s book This is My God appeared in a special National Dinner issue of the OU’s Jewish Action newsletter in May 1959 (see highlighted square). Wouk was a member of the OU’s board of directors at the time. Courtesy of the Yeshiva University Archives, Benjamin Koenigsberg Papers, 9/4.

On my bar mitzvah, my late father, Rabbi A.H. Lapin, z”l , began teaching me that we judge our world by the Torah and never the reverse. His example was the tourist who stood in the Louvre gazing critically at Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Finally, he shook his head and muttered, “I just don’t see what the fuss is all about.” At which the Parisian gendarme guarding the famous painting responded, “Sir, when you stand in front of the Mona Lisa, you are on trial, not the painting.” My father explained that he never wanted to hear me say about any Torah he taught me, “That makes no sense.” “If you don’t understand it, that’s because you don’t make sense,” he insisted. The lesson is that we measure all by the Torah, never the other way around. Wouk clearly knew this lesson from at least his early forties. It shaped his relationships, his work, his involvement with Torah communities around the country as well as his long and loving relationship with the Orthodox Union.

We recently bade farewell to Herman Wouk. His repute will only grow in both the worlds of American literature and Torah Judaism. The descendants of anyone privileged to have known him will far into the future be telling their children of how their great-grandparents actually knew Wouk.

Though he’s no longer with us in body, it’s easy to know where Herman Wouk is and what he’s doing. Towards the end of This Is My God, Wouk described how after 120 years, every Jew will arrive in the Olam HaEmet and find “ . . . the Lawgiver in the end waiting for you. He will greet you with the smile and the embrace of my grandfather. ‘What kept you so long?’ he will say. And you will sit down to study the Torah together.”

Rabbi Daniel Lapin, president of the American Alliance of Jews and Christians, and his wife Susan have authored seven books and together host a daily television show on the TCT Television Network. The couple, who live in Baltimore, Maryland, speak for dozens of synagogues, Shabbatons and business groups every year in the United States and in countries around the globe.